Are You Asleep or Just Ignoring Me? Parents, Kids, College, and Communicating

Each summer, through our summer orientation program, I get the chance to meet excited – and nervous – students and their families as they are beginning their college journey. It is one of the things I really like about the structure of orientation at Boston University; students and parents come to orientation weeks, and sometimes even months, before the actual college experience begins. Why is this cool? Because it allows the rest of the summer for families to have the follow-up conversations about how things will change when college begins.

There are so many things that are ripe for discussion and, frankly, planning.

How many times each week or – OY! – each day do we talk on the phone? Does texting count as talking?

How specifically do we talk about how classes are going? Is there an expectation that exact grades on papers or tests are to be shared?

Here’s a tough one…what do we think about drinking? (Let us not be so naïve as to think that there is never access ever to alcohol by underage students.)

Is it a good idea to get a part-time job? How will money be handled between us?

Homesickness. How do we handle it? For that matter, “kidsickness?” (Not to be underestimated is the transition for the parent. I have seen many have a much harder time with the transition than the college student him or herself.)

Then of course there are the larger, more substantial questions… What are the goals for this first year of school? What is important? What does “success” this year look like?

When I talk to students and parents at orientation, I always mention the importance of these conversations, and how lucky they are to begin thinking about and discussing these issues NOW. Even just driving home from the two-day orientation program and asking the simple question of “So, what did you think?” can open a huge door for dialogue. And who initiates, kid or parent? Who cares? These are important questions for or from either. The whole point is to establish a discourse that can continue throughout the summer and into the school year, one that will help to create a shared understanding of expectations on these and other issues. This is not to say that you can head off any adjustments or hurdles, but you can come to agreement – or at least compromise – on what some of the answers will be. I might add, how you will talk about and work through the unanticipated, the unplanned.

There is no one path for success, but you can create your own blueprint for communication in this next phase of the parent-child relationship. And, if I may be so bold, it is generally best to not wait until that final drop-off at the end of the summer.

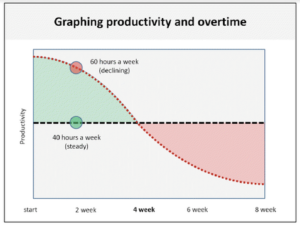

I’ve done some research in flexible work environments, and have found that such arrangements can indeed increase productivity – though the opportunities obviously are relative to the place and nature of the work. For example, research shows that “compressed work weeks” (like a five day schedule being consolidated into four days) can reduce absenteeism and increase productivity anywhere from 10 to 70 percent. And studies have shown that short breaks allow people to maintain their focus on a task without the loss of quality that normally occurs over time. Moreover, Google has employed a “20% time” approach, wherein their employees spend one day a week working on projects that aren’t necessarily in their job descriptions – to develop something new, or fix something they see as broken, or really most anything. The 20% time approach has brought about serious innovations such as Gmail, Google Reader, and more. (Full disclaimer: it was reported a while back, though both unsubstantiated and disputed, that Google may have killed this workplace perk, one that has been considered as a real competitive advantage to the company.)

I’ve done some research in flexible work environments, and have found that such arrangements can indeed increase productivity – though the opportunities obviously are relative to the place and nature of the work. For example, research shows that “compressed work weeks” (like a five day schedule being consolidated into four days) can reduce absenteeism and increase productivity anywhere from 10 to 70 percent. And studies have shown that short breaks allow people to maintain their focus on a task without the loss of quality that normally occurs over time. Moreover, Google has employed a “20% time” approach, wherein their employees spend one day a week working on projects that aren’t necessarily in their job descriptions – to develop something new, or fix something they see as broken, or really most anything. The 20% time approach has brought about serious innovations such as Gmail, Google Reader, and more. (Full disclaimer: it was reported a while back, though both unsubstantiated and disputed, that Google may have killed this workplace perk, one that has been considered as a real competitive advantage to the company.)